This is a story told by the National Child Labor Committee to persuade Americans to support the regulation and elimination of child labor. from the original Child Labor Bulletin, Ohio State University Library

Our warm friend, Mr. Coal of Pennsylvania,

tells us:

I lay snug and comfortable for many years, way down in the middle of a large mountain, until I grew into a great big coal.

|

|

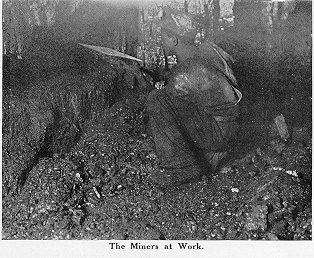

One day a sharp steel pick cut through

the rocks and I was pulled down from my bed and fell to the ground. All was

so dark, I could have seen nothing if it had not been for tiny lamps which two

men wore in their caps. The men were miners, digging for coal.

My former neighbor, old Mr. Wise Coal, soon fell beside me. He used to tell about the great world outside, where every one, to be really good, must make someone else happy. When he heard the picks he said, "We are going there now, and we will make some children and grownups warm and comfortable. But I am sad when I think of the little boys who must help take us there. Watch to see what happens and you will understand."

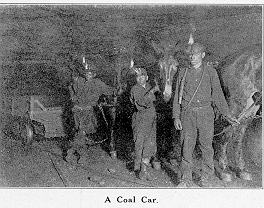

A coal car, drawn by mules, came along.

I thought they must he men, who threw us in and drove the mules; but on looking

closely I found that one of them was a boy about 12 years old. My companion

shook his head. "It is only half past seven o'clock in the morning. Boys of

his age should be eating breakfast and getting ready for school," he said.

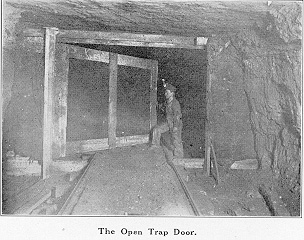

Driving through the mine we came to

a big trap door. "When men work in mines, air is forced in to them from the

outside," said old Mr. Wise Coal. "The trap doors must be kept closed so that

the air will go where the men are working. Boys open and close these trap doors

for the cars to pass from one chamber to the other. They are called trapper

boys.

|

|

|

|

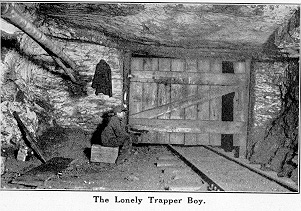

"Look back and see how lonely this one is" I heard him cough and tell one of the drivers that medicine didn't help him anymore. The mine was so damp, he always got a new cold."

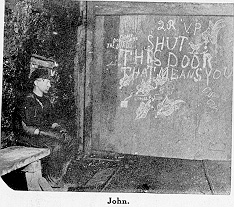

The next trapper boy we passed was

John. John wanted to go to school but his parents made him work. They didn't

know that he could earn better wages later, if he went to school now. The trap

door was the nearest thing to a blackboard he had, so he drew pictures on that.

John liked birds, and couldn't see any outofdoors, because

it was after dark evenings when he left the mine. So he drew them on the trap

door, and played they were alive and he wrote on the door, "Don't scare the

birds!" and this was all the fun he had.

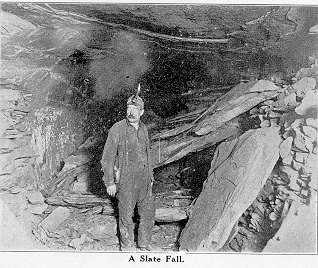

When we passed a place where the roof

had caved in, old Mr. Wise Coal shuddered. "I hope no boys and men are buried

there." he said, "they often get killed in that way."

As we came out of the mine we met James.

They call him "a greaser" because he has to keep the axles of the car greased

so that they run smoothly. He had grease all over himself and his clothes.

|

|

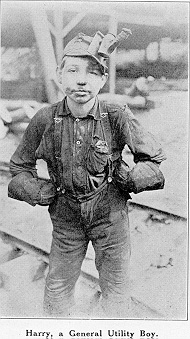

Next we met Harry. He does odd jobs

about the mine. When he first started at work, he wanted to go to school, but

now he does not care. He is too tired to think about it, even.

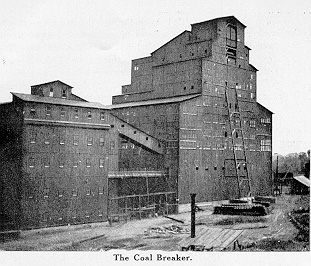

At last our car full of coal came to

a building, called a "coal breaker." Here the coal was put into great machines,

and broken into pieces the right size for burning.

|

|

|

|

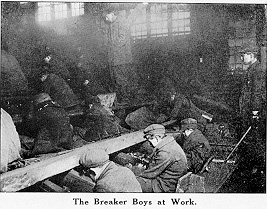

Then the pieces rattled down through

long chutes, at which the breaker boys sat. These boys picked out the pieces

of slate and stone that cannot burn. It's like sitting in a coal bin all day

long, except that the coal its always movie;, and clattering and cuts their

fingers. Sometimes the boys wear lamps in their caps to help them see through

the thick dust. They bend over the chutes until their backs ache, and they get

tired and sick because they have to breathe coal dust instead of good, pure

air.

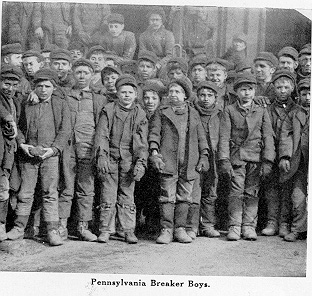

Hundreds and hundreds of boys work

in the mines and in the breakers from early morning until evening, instead of

going to school and playing outdoors.

Do you suppose the little fellows sitting

all alone in the deep coal mine, or bending over the chutes, ever think of the

merry children sitting around the burning coal?

This bright room is better than the

dark mine. The happy talk is better than the silence. The warm fire glow is

better than the cold.

Do you suppose that the happy children

made warm by the coal ever think of the boys who helped to get it ready for

them?

Do they think of the children who make

medicine bottles in glass factories and cotton dresses in mills and tenement homes?

What can these children who play around

the fire do to help the boys and girls who work in mines and factories? They

can do this:

They can ask their fathers and mothers

to make laws to help these other children. Fathers and mothers can make laws.

They know how to make laws that will kelp children. They also know how to make

sure that the laws are obeyed.

Sometimes fathers and mothers are so busy taking care of their own children-the children round the fire at home-that they forget the others-the children in mines and factories. But we must not let them forget the other children The most important matter in the world is, that all the children-all the children -- shall grow up healthy and intelligent and good.

Note:

Our research tells us that in the 1800's there were no children working underground

in the Castlecomer Mines (children being under 14 years of age)

Click for short report