Miners lying on their sides in a confined area, digging out the coal

| These are some related stories that we discovered about mining conditions in Pennsylvania. It is reported that many miners from Castlecomer actually emigrated to Pennsylvania. We have had contact from a decendent of one of these miners – Dan Kerwick who is very interested in our project. He told us “This was my ancestors birthplace and many of them worked the mines” |

|

|

|

Miners lying on their sides in a confined area, digging out the coal |

This page gives details of the many dangers facing a miner from the time they go down underground until they re- surface after their days work. There were many dangers facing the miner such as flooding, cave –ins, rockfalls, danger from machinery & cables, dynamite etc. It also mentions the health danger from constantly breathing in coal dust and how, many miners suffered from it for years afterwards. Some miners were badly hurt and even killed.

The coal dust was also very dangerous. It was a slow killer and after years of breathing in the dust, many miners developed the miners lung disease known as "Pneumoconiosis" which generally killed them.

Many miners were understandably scared going down in the mine because of the dangers but nevertheless they soldiered on as they had to put bread on the table for their families.

5 + 4 does not make 10. Example of "minor" mining accident - The miner "only" lost a finger !!

Air Conditioning

Air conditioning was a

problem for early miners. At first it was mastered by burning coal at the bottom

of a working shaft or air shaft and this made an air current. Steam driven fans

to air the coal workings were used at the Jarrow pit in the late 1800s. This improved

working conditions.

Drainage

Water was the early mine owner's greatest problem. Where his workings were on hilly ground, he could drive a water level or sough to daylight. In other cases, his water level discharged water into a well (a sump) from which it could be wound out by bucket or pumped out by a primitive horse- driven gin like the rag and chain pump or chain of buckets. Not until the introduction of the Newcomen engine in the early eighteenth century was there a reliable device for draining mines at any great depth. At Peggs Green in Leicestershire, a steam engine installed in 1805 and typical of the period discharged 750 gallons (3,410 litres) of water a minute. Some collieries are far wetter than others, but a typical deep mine of the 1980s would discharge about 200,000 gallons (900,000 litres) a month, although some discharge over a million gallons (4.5 million litres) a month, using electrically driven pumps, mostly of the submersible type, which have replaced steam engines.

A great deal of water is encountered in sinking

shafts; Shafts, once sunk, are kept dry by lining

them with tubbing. In the eighteenth century, this was made like a wooden cask

or tub (hence the name) but iron came into use in the nineteenth century. In the

South Wales valleys, where pit tips are often on hillsides, water has at times

made the tips unstable, as at Aberfan, where 144 men, women and children were

killed by a slippage of colliery spoil in 1966. Special care is taken to ensure

that this can never be repeated.

Ventilation

In early mining practice, ventilation was achieved by linking together two shafts and allowing air to flow between them by natural convection. The flow of air could be improved by suspending a fire basket (like a nightwatchman's brazier) in one of the shafts. The warm air rising in the up- cast shaft caused a partial vacuum in the workings and cold air flowed down the downcast shaft to maintain the balance of the air pressure. A few collieries used fire baskets in the seventeenth century, but the practice did not become widespread until the eighteenth.

In 1787 an underground ventilation furnace was built at Wallsend Colliery near Newcastle in England and owners of other deep mines soon adopted the practice. Whilst a large furnace undoubtedly improved ventilation, there was always the danger of explosion from gas-laden air passing over the fire. This danger was eliminated in the early nineteenth century by isolating the foul air from the fire by means of a dumb drift.

From the mid nineteenth

century mechanical fans began to replace furnaces but the last of these (at

Walsall Wood Colliery, West Midlands) did not go out of use until 1950. To guide

the air round the workings it is necessary to have a system of doors and

stoppings. Nowadays the doors are spring- loaded, but up to the mid nineteenth

century boys called trappers were employed to close the doors after ponies had

passed.

Gas

The main mine gases are chokedamp (or blackdamp) and firedamp. As its name indicates, chokedamp makes breathing difficult, and, in high concentration, impossible. Firedamp is not poisonous but when mixed with air in the proportions of between five and fifteen parts per hundred, it is explosive. Efficient ventilation dilutes these gases at the same time as it provides reasonably clean air to breathe. However, in the early nineteenth century ventilation of the deep, gassy mines of Northumberland, Durham and Cumberland in England was not efficient, and there were many explosions resulting from the use of candles. Castlecomer mines did not have these problems as there was no gas in the coal and as such a naked flame could be safely used.

It was

not until Sir Humphry Davy's invention of his safety lamp in 1815 that miners in

England were provided with a safe light. Here, the flame of an oil lamp was completely

surrounded by gauze, which distributed the heat of the flame over its surface

area so that at no one point was the gauze hot enough to fire an explosive

mixture. Modern safety lamps, still based on Davy's principle, are used for gas

testing. Illumination was later provided by electricity but besides the fixed electric

lights on the main roadways, every miner has a cap lamp which gave a brilliant

light.

Underground Haulage

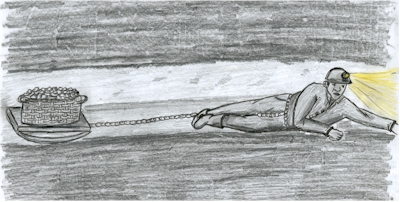

In the early mining days a person who pulled a basket or container by a rope or chain was called a "Hauler". The apparatus that he hauled the basket with was called “gurl and swivel” which was a girdle and chain. A chain was connected to the girdle around the hauler’s body. In the Castlecomer mines we were told that through the ages the miners were very proud of the “gurl and swivel” in fact so proud that they polished the gurl and swivel for Sunday and special occasions.

|

|

Early haulage- Gurl & Swivel hauling basket on sleigh |

|

|

|

Boy using a gurl & swivel to haul a tram |

Sleighs

An improvement on the baskets was the drawing of a "Sleigh" (a wooden box) along wooden poles, which were later refined to primitive wooden tracks. The tracks gave a reasonably smooth surface to pull on and the sleigh would glide along the moist timber. Boys and girls were ideal for this work especially in the more confined roads close to the coalface

|

|

Runners from an old sleigh found at mines in the "Upperhills" |

Hurriers and Thrusters

In

Lady Anne Wandesfordes' time (which was 1754-1830) the mines were operated under a leasing

system initiated by lady Ormonde. Normally there was a team of 50, which was made up of cleaners, cutters,

breakers, hurriers and thrusters. Hurriers and thrusters were hauliers, that

pulled a sleigh by a draw bar. The sleigh carried 3 ½ cwt. Hurriers

pulled

and were helped by the thrusters who pushed from behind. Hurriers were paid

2 shillings a day and the Thrusters were paid 1s 8d. Teams were organised by master

colliers and were paid by token paper which might or might not be honoured at

the masters grocery shop. A wheel is locally called a “reely” so when wheels

replaced the sleigh the coal yard depot became known as the reely yard and so we

got the local place name the “Railyard”.

Trammers

With the introduction of the wheel came a box or “tram” which was initially run along wooden and later along iron rails. Up to 1925 the box was made of wood but after 1925 the Deerpark miners in Castlecomer used trams made of iron. The trammer was the name given to the man that operated the trams. He and a helper were paid in the 1920’s according to distance and later according to tonnage. A token was put on the tram. The language used by the trammers was quite colourful such as “Darby’s drift “ “no. 9 coal” etc. Various names were assigned to men and boys working the trams. A "Trammer" or "Hurrier" or "Thruster" pushed the trams. A "Hauler" pulled the tram. A "filler" filled the trams.

The wheels of the old wooden trams were often used to draw barrels of

water along the roads in the

Colliery area , before road side pumps or piped water was available.

Richard

Sutcliff invented the conveyor belt in 1905. This made life much easier for the

miners but it did away with the “Trammer”

|

|

|

Trammers arriving at the mouth of the pit with loaded trams |

Pit Ponies

Pit ponies were used for

underground hauling at the Rock and Vera Collieries between 1910 and 1925. There

was an underground roadway between the Rock, Vera and old Rock pits. In 1915 the

mining authorities sent to Durham for pit ponies as ponies of the right size

were not found in Ireland. These ponies worked underground and were usually

blind when they retired.