Unemployment For 180 Men

Extract from the Kilkenny People the day Deerpark

Mine closed

AT

FOUR O'CLOCK today (Friday 31st. Jan. 1969) an era will end. Coal mining

in Castlecomer will cease. Over 180 men will join the unemployed and a

grim two-year struggle to save the mines will bow to defeat.

Government help for Castlecomer Collieries has been

terminated and the mines, which for generations have been the bread and

butter of Castlecomer, have been sentenced to death.

As the last shift leaves the pits today, Castlecomer

mines will grind to a permanent halt and the chill silence of dead jobs

will descend over the black mines at Deerpark with an unprecedented

finality.

For, unlike previous crises hope now for the mines is

almost non-existent. Even the huge pumps which hourly spewed up thousands

of gallons of water from the coal tunnels are to be switched off leaving

the mines to drown slowly but inevitably.

LAST

EFFORTS

At

the time of going to press, last efforts were being made by the workers'

union, the ITGWU to at least postpone the closure.

But all appearances were that the efforts would be in vain.

The closure became a reality only on Wednesday of

last week when word was received from the Department of Industry and

Commerce that no more money would be made available to the collieries.

Immediately, one week’s notice was given to almost 200 workers,

the majority of whom are married men with large families, but curiously,

the end has been accepted with a strange resignation by the miners.

GOOD

SPIRITS

When

our representatives visited Deerpark during the week they found the men in

unexpected good spirits. Laughing and joking creating an atmosphere, which

belied there blackened faces. Wet clothes and the prospect of almost

immediate unemployment. “Miners are different to everyone else".

Someone said. "Miners

aren't made. They're born

from generations of miners. They

work hard and live hard. Their

life is so hard that even a knock like this can be accepted".

But

the reality was still there. "I've been working in-the mines now for

30 years", Mr Eamonn Geoghegan of Moneenroe, told us.

'It's now too late for me to emigrate. I have a wife and nine

children. I just can't pull up roots and go.

I'll have to try and get work as near to home as possible.”

TOO

OLD FOR ENGLAND.

There

are lots of fellows here like me - too old now to go to England.

Some of them have 13 and 14 children. I don't know what we’re

going to do". This was the general feeling. No one has plans. The end

came too suddenly. Many are pinning their hopes on one of the new

factories, which are scheduled for Castlecomer. But what worries them

mostly is the time lapse between the closure of the mines and the opening

of the factories.

At present only one factory is in the course of

construction – the huge Castlecomer Mills, which when completed, will

employ a total of over 70 (30 men and women exclusive of management and

clerical staff).

The other three factories scheduled

for Castlecomer – Kilkenny products, Carroll System Buildings Ltd. and

the Sisk –Mc-Gregor brick works – have not yet been started

Mr James Brennan of Moneenroe will be looking for work at one of

the factories. But he’s worried about what will happen if they are not

completed.

“I have a wife and 9 children and I may have to go to England”

he told us “I am very sorry to see the mines closing. I have been

working at the coalface for 30 years

OVER

50 YEARS

Mr.

Willie Mealy of the Brook, Moneenroe is one of the collieries longest

serving employees. He started work in 1917 at the age of 14. “Now at 66

with 52 years of mining work behind me, I must turn around and look for

another job”, he said.

I just don’t know what I’ll do,” said Mr Terry Nolan of

Coolnaleen, Clogh, who has been a rope man for 32 years. “I suppose I

will have to look for a job in the handiest place I will get it.”

VERY

UPSET

Particularly upset about the closure is Mr Nicholas Boran, the man

who, perhaps more than any other, has been responsible for keeping the

mines going for so long

Mr Boran began his mining career at the coalface. In the thirties

he became a check weight man and during the mine crisis in 1965 he became the workers’ representative on

the Board of Directors.

Mr Boran said the real tragedy of the mines was the demand for coal

was so great that it completely outstripped the supply.

“Castlecomer coal is the finest in Europe.” He said.” And now

we are going to bury it for good. We will have to import considerable

quantities of inferior foreign coal, which will require about twice the

tonnage to give the same heat as Castlecomer coal.

This will no doubt adversely effect Ireland’s balance of payments

“We in the ITGWU would like to see the Government nationalising the

coal industry and developing the Castlecomer mines as they should be

developed. They could be run economically.

MINE

HISTORY

Mr Boran outlined the recent history of the mines for us.

On July 31st. 1965. the Board of Directors closed the mines

following the Powell- Dufferin report that said there was no more

economically extractable coal available.

Over 330 men lost their jobs.

Moves to save the mines immediately began. Four boreholes made

during a geological survey indicated that there was in fact plenty of

economically extractable coal in the area.

The ITGWU employed an English mining engineer Mr. Bathurst, to

carry out a survey and he recommended driving a 1,000-foot tunnel through

the wash-out (caused by a subterranean stream washing away the coal),

which was responsible for the closure.

The Government promised financial help and on November 8th. 1965, the

mines reopened, with over 180 men returning to work.

When 600 feet of new tunnel was completed coal was met again and the last 300

feet of the suggested 1,000 feet drive, produced very workable coal.

In the meantime, however miners working on a second coalface in the

"Catbrook" area reached a washout one year before the Powell-Dufferin Report

said they would.

BIG

PROBLEM

The Colliery were faced with the problem of laying off skilled men

whom they would need later on when the tunnel through the wash-out was

completed, or absorbing them into a situation which was not yet ready for

the men. They decided upon the latter.

During the last two years: approximately £200,000 has been given

to the mines in grants. But it is pointed out that over £100,000 has gone

back to the Government again in income, turnover and other taxes.

In September of 1968, more money was sought from the Government

without success.

The

money,

another £200,000 was needed

to improve conditions, replace obsolete equipment, essential for economic development of the

mines, drive

another 1,000 foot tunnel to the area where geological survey borings showed there was workable

coal and provide plant for the manufacturing of briquettes from slack.

This, Mr Boran is convinced would have made the mines economically

viable.

In

England, he said, the government realised that money had to be spent on

mines to make them economical units.

The money, in some cases up to one million, was spent and the mines made money. The same could be done with Castlecomer. But it looked now that Castlecomer mines would die.

One of the principal criticisms of the government in Castlecomer is

that if the mines were doomed to close they should have been phased out as

jobs became available in the factories scheduled to be built.

In

the end the blow has come too fast- and too hard.

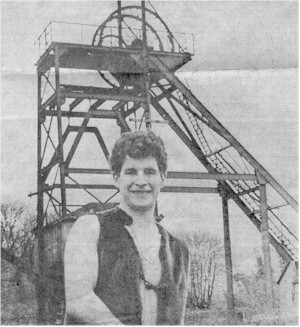

Tom Coughlan (R.I.P.)

The Last Miner to surface from the "Deerpark" Pit