Nixie

Boran & The Castlecomer mine & quarry Union

Origins of Coal (click)

The Freeman's Journal

To understand why coal was found in the Castlecomer plateau you have to imagine how the area would have looked during the Carboniferous period. It was during this period that the formation of coal seams actually began. A fault (movement of the earths crust) occurred and this explains why coal was found on the level ground and again on higher ground. Coal mining developed into a very important industry. The Wandesfordes and their tenants did much to help the development of the area and the villages of Clogh and Moneenroe grew into the pleasant places we now know. Under the influence of the landlords and the Middlemen Castlecomer developed. Even though the mines closed, Castlecomer continued to grow and today has many fond memories of a true mining tradition.

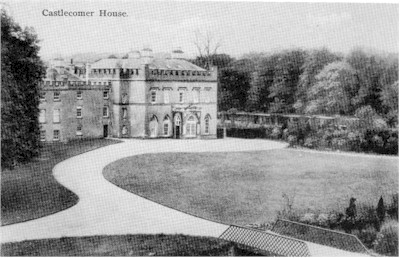

Castlecomer House - home of the Wandesforde family

An account of Coalmining in Castlecomer by the last owner....

Coal – or more correctly Anthracite coal – has been mined in the Castlecomer region since about 1640 – that is over 300 years.

Geology

– Perhaps it would be as well firstly to give a few notes on the

geology of the district, avoiding, as far as possible, technical terms.

One has to put one’s imagination to work from the very start.- a very

difficult task because we have to go back some two hundred and forty

million years – 240,000,000! A very different world it was then – a

flat land, hot and steamy. Huge swamps existed, full of thick

vegetation, some of it like enormous ferns. It is from this swamp

material that coal is derived.

Age followed age - some periods dry and hot, others hot and moist, some

cold, some very

cold when thick ice and glaciers moved slowly over the land. At

other times the whole land sunk beneath the ocean, limestone was formed

under the seas to reappear when once more the land rose. Gradually, the

rocks cooled and buckled, mountains pushed up, volcanoes burst forth and

lava poured down. As countless ages passed, the vegetation of the swamps

was covered up and compressed by millions of tons of mud and sand which

formed into shales and sandstones. In the case of anthracite the

pressures were so great that practically all the gases were pressed out.

Many

of those different epochs recurred again and again - that is the reason

why there are various seams of coal at different depths. Sometimes a

whole mass of rocks split, one part moving downwards or upwards- these

movements gave rise to what is known as Faults - there is a huge one on

or about the Coolbawn Hills - a Fault of some three hundred feet so that

the seams of coal which lay beneath the flat land between Crettyard

and Coolbawn were pushed up and are found again on the top of the

Coolbawn hills.

THE CASTLECOMER COAL-FIELD.

In this area there were three seams of sufficient thickness to be of economic value. Starting from the surface of the land, the first seam is (or rather was , before been extracted ) “The Three Foot Seam”. This lies between 50 and 100 feet from the surface and lies in a wide band from roughly Doonane to Coolbawn and extending from Clogh to the foot of the Coolbawn hills. Because of the aforementioned Coolbawn Fault it occurs again above the Coolbawn hills but does not extend very far to the east. This three foot seam was a very high quality anthracite and being so shallow, was easily worked. The next seam is the Jarrow –about 200 feet below the three foot. A peculiar feature of this seam is that there is a “channel”or horse –shoe shaped belt ,lying between Doonane, along Moneenroe to Coolbawn where the coal is much thicker and of better quality than over the area on each side. In the “Channel” the coal was sometimes 4 feet thick, whereas the outlying coal is only some 8 to 9 inches thick and so not economic to mine except to open-cast it where it comes near the surface.

Lastly,

another 300 feet or so, comes the Skehana seam – a very high quality

coal , acknowledged by geologists to be the best quality anthracite

found either in England or Europe, but only of comparatively small

extent.

A Geological feature connected with the Skehana seam is what is known as a “Wash-out”. This means that at some time in the distant past when the coal still consisted of vegetable matter, a lake or ancient river flowed in, cutting out the material which would have become coal and deposited sand which became sandstone.

This is often found in coal fields and such “washouts” may be quiet small or very large- the latter being the case in the Skehana seam.

SHORT

HISTORY OF MINING IN THE CASTLECOMER AREA

As

far as is known, some coal may have been worked by primitive methods as

early as 1600. Coal seams are usually tilted and very often at some points

they come out to the surface- in mining language such appearances are

called “Outcrops”. Naturally, it is comparatively easy to get at such

coals and undoubtedly such outcrops in the ‘Comer area were worked.

About

1640 when mining of the old Three Foot seam started, iron was also

produced. This was in the form of heavy spherical lumps of iron pyrites

which are sometimes found associated with coal- particularly in the Jarrow

seam. These iron balls were then smelted and the iron extracted and there

are still some old gates and railings around Castlecomer which were made

from Castlecomer iron.

To

return to the old Three Foot seam- in or about 1640 efforts were made to

mine this seam. The method employed was what is known as Bell Pits. It is

well to remember that no explosives existed at this time- so that to get

at the coal, the overlying rock had to be broken by wedges, hammers and so

on.

First

of all, two shafts were sunk from 25 to 50 yards apart. Then the first

mining operation was to connect these two shafts by an underground passage

or “level”. This was essential in order to give ventilation to

subsequent mining. Once this main level had been driven miners then

began to extract the coal on each side. Of course, they could not take out

all the coal- otherwise the rock above them or the roof would have

collapsed on them- and so, at intervals, they left in round or rectangular

pillars of coal for support. Sometimes there is evidence of miners having

re-entered a working bell-pit mine in order to take out some of these

pillars- “robbing the pillars” it was known as- a very dangerous

proceeding, but these “old miners” were most skilled and wonderful

men. Only recently during some “open-cast” workings, these old

workings have been laid bare and the remaining pillars could be seen. The

“runner” of an old sleigh was also found during this open-casting.

These sleighs were used by the “old men” to pull the extracted coal

along their very low passages or “levels”.

THE

BELL-PIT MINING ORGANISATION

During

the 17th century when this type of mining was being used, the practice was

for the owner to sink each of Bell Pits. He then made a bargain with

the men called “Masters Miners” to extract the coal at so much per

cubic yard. The Master Miner then collected together as many miners as he

required, agreed their renumeration and all set to work to “win”

the coal. By this old method the Three Foot was mostly extracted- in later

years more sophisticated methods being used. It has been estimated that

some 11 million tons were taken out before this seam was exhausted.

THE

JARROW SEAM

At the end of the 18th century- about 1740- this seam was discovered, lying about 200 feet from the surface. By this time mining had become more developed – explosives were available and steam power for pumping, haulages etc. Pits were successively sunk all along this aforesaid “Channel”, starting near Doonane and reaching near to Coolbawn. Eventually some seven Jarrow Pits were sunk – one after the other had become worked out.

Pits

on the “up-throw” were also sunk and worked such as the “Ridge”,

the “Rock” and the “Vera”. At one time, early in the nineteen

hundreds, owing to the enterprise of Capt. R.H.Prior Wandesford an aerial

ropeway was constructed, running above the country between the various

Jarrow pits and the new Skehana pit.

THE

SKEHANA SEAM

In 1924 an inclined shaft or “Drift” was sunk to this seam in the Deerpark and became known as the “Deerpark Pit”. A few years before, a pit had been sunk to the same seam to the west of the Skehana road but proved a failure owing to geological features and was closed.

The Deerpark was worked from 1925 until 1969. Its deepest point was eventually some 700 feet deep from the surface and some 11 miles of underground roadways had been constructed.

At first and for many years the pit generated its own electric current by steam generators, but laterally, when the ESB was available, all electric current was supplied from this source- three power lines coming to the pit at 30,000 volts and this was then transformed down for use in the various machinery in the pit. Since about 1945 all mining was by machine, that is, there were electric coal cutters, underground conveyers, haulages and pumps. Pumping was one of the most costly items- some 60,000 gallons having to be pumped out per hour.

The coal was sorted, cleaned and sized on the surface at an installation known as “The Screens”. There were also up-to-date miners baths, for along time the only proper miners baths in Ireland. In 1917 a branch railway line was brought from Kilkenny but after the second World War this was discontinued as lorry transport had become a more economic proposition.

Up to about 1952 conditions in the pit were satisfactory but at about this time the “Wash-out” (see above) was met and in addition , the character of the seam changed so that it became more and more difficult to extract.

Finally,

in 1969 the mine was completely uneconomic- the loss per week being

some £2000. For some time, the Government had subsidised the business and

every effort was made and expert overseas opinion sought but all to

no avail and so the pit was forced to close.

OWNERSHIP,

MANAGEMENT AND EMPLOYMENT

Ever since 1637 the mines have been owned by the Wandesforde family. The first Wandesforde to come to Ireland was Christopher Wandesforde who came over from Yorkshire with his friend Thomas Wentworth who became Lord Strafford who was Governor of Ireland. Christopher Wandesforde was made Master of the Rolls- a legal appoinment- and when in 1640 his chief,

Lord Stafford, was arrested and taken to England to stand trial, Wandesforde was made Deputy Governer of Ireland. Shortly after Lord Stafford was executed, Christopher Wandesforde died. It was him and his grandson – another Christopher Wandesforde – who started the mining to any extent. At various times the mines were leased by the Wandesfordes to others- the last long lease being to the Dobbs family and it was during their lease that most of the Jarrow seam was worked. When Capt. R.H.Prior-Wandesforde succeeded to the property at the end of the 19th century he took over all the mining and extended it very considerably, supplementing capital from the sale of certain lands in Yorkshire.

In

1917 a Private Company was formed the bulk of the shares being held by the

Wandesforde family. The last Managing Director was the writer of this

short history-Capt.R.H.Prior-Wandesforde (Capt. Dick).

Pit managers always of course under the law, properly qualified Mining Engineers have held position of managers – at times there were, in addition Deputy Managers or Underground Managers.

Many

of these Managers were “characters”- the best being “tough” men

,but judt. Many men in the district will still have memories of such

managers as Mr. Whittaker, Mr. Hargreaves and of course our last manager

Mr. Jim Bambling.

Employment –At one time – between the two World Wars- almost 1,000 men were directly and indirectly employed. Later, as pits closed, this number was reduced to about 400 and at the end even less.

Castlecomer, Moneenroe and Clogh were of a true mining community and many are the family names which keep recurring as miners.

May this tradition never be lost, nor the names of those men who made it.

Written by R.C.Prior-Wandesforde- last Managing Director of Castlecomer Colleries Ltd.

November

1972

Steam pumps were introduced into the Kilkenny coal field in the early decades of the nineteenth century, and steam, was used to drive the machinery until the advent of electricity. Pit ponies were used to transport the coal underground right up to the 1950s. In 1842 a commission set up by the British government to investigate the employment of children issued a report on children working in mines in the United Kingdom. Frederick Roper, one of the commissioners, visited mines in the south of Ireland. Writing about the coal field on the borders of Kilkenny and Laois, or Queen's County as it was then called, he said: "I inspected about a dozen of the different shafts, worked by contractors and found none but men employed. Indeed, I was informed that none but strong, able young men would be of any use in the pits, the labour being severe. I did not see any under eighteen years of age".

He goes on to say that he went down into the pit and saw the people at their work and even the "hurriers" who draw the coals to the foot of the shaft, were mostly strong young men. Elsewhere, Roper stated that no female of any age was employed in mining. It was not necessary to employ child labour as there was a surplus of adult workers. He described the 'hurriers' in the collieries of Kilkenny - Queen's County going along the narrow low passages of seldom more than three feet high and often down on their hands and feet, the body stretched out, they drew the sledge, on which wooden boxes containing the coal are placed, by a girdle round the loins and a long chain fastened to the sledge going down between the legs. It was a matter of wonderment to me how these hurriers many of whom were stout men upwards of six feet high, could manage to get along these very narrow low passages at such a rate as they do.

Roper himself found it difficult to crawl through the passages. The

'hurriers' complained that their work was very hard, there were neither

railways nor tramways in the pits and that boxes of coal had to be pulled

along the uneven ground on sledges. Strong men were required for this kind

of heavy work.

Just before the outbreak of the first World War another seam was discovered at Skehana. This was first worked at a pit in West Skehana and then at the Deerpark, which opened in 1924. This coal proved to be of a high quality and compared with the best anthracite found anywhere in the world, being practically free of sulphur, and of good heating power. By the early nineteen thirties there were five major pits in the Castlecomer coalfield, The Jarrow, The Deerpark, The Rock Bog, The Monteen and The Vera, named after the Wandesfordes eldest daughter. The Wandesfordes owned, and except for brief periods of leasing, ran the mines. In the late 1880s Captain R.H. Prior-Wandesforde inherited the family estate. He inherited a position of great power in the area. The family had amassed a substantial fortune from mining and owned thousands of acres of woodland and farmland as well as the game and fishing rights of this land.

The Captain had a great interest in the mines and carried out

considerable expansions. He had an overhead ropeway constructed, connecting

the various mines, so that the coal could be brought together at a point in

the Deerpark, where there was a

terminus, for a branch train-line that carried it to Kilkenny. He was a

paternal autocrat who looked on the miners not so much as his employees

but as his people. In manner he was withdrawn and reserved, and regarded

by the men as stern and hard. Most

of the miners in the nineteen twenties saw him as their total lord and

master, determining salaries and conditions. Normally the agent or his

officials presented them with a contract and they accepted what they were

offered. The family boasted of never having yielded to pressure or to

strikes.