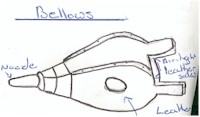

Bellows

|

|

|

Raising

the fires temperatures sufficiently to enable iron to be worked requires a

forced draught. From the earliest times this was provided by a bellows which

could be as much as six feet across. The bellows

produced a draught on both the up and down strokes delivering it through a cast-

iron tube called a layere to the heart of the fire. They were operated by a

handle projecting out over the forge at around shoulder height, either by the

smith himself or by a labourer or apprentice or compliant passer by. It was

skilled work, as pumping too vigorously, or too lazily could prove

disastrous. Heat iron too fast and it becomes brittle; heat it too slowly and it

melts and burns. Wrought iron can be worked at a wide range of

Snowball heat, beyond which iron melts, makes the metal white hot and spongy. At

this heat two pieces of metal can be fused by hammering. Below this are the:

welding heat, full, light and slippery-which are most often used.

Next comes

bright red, cherry red and dull red which are used for shaping metal and

flattening, smoothing and finishing.

Then there is black heat just enough to make

the iron glow faintly in deep shadow.

Lowest of all is warm heat, where the metal

is wafted through the fire rather than held in it until it is just too hot to

hold. This heat is used for setting up springs