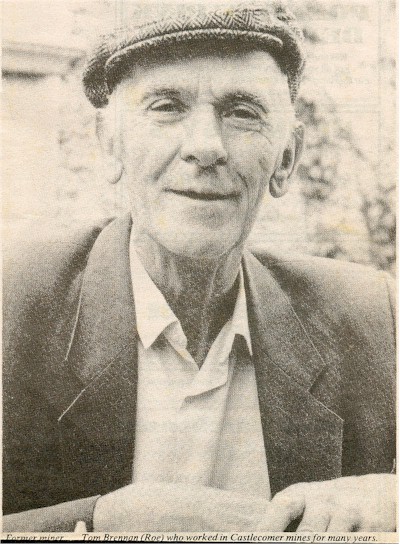

Tom

Brennan (Roe) R.I.P. in an interview

taken a few years before his death

TOM

BRENNAN (Roe) is as much a coal miner today as he was 50 years ago when he

began work at the coal face in the Deerpark Colliery at the tender age of

14.

Despite the fact that he is now retired and he has not worked in a mine for 19 years, Tom still retains his passion for mining. It takes just a few simple questions about mining to ignite that passion and to have it blazing. Stories about the good old days trip off his tongue. The people, the crack, the camaraderie, the hard work.

It's

a fiery passion that plays down the cramped, dangerous conditions more

than 700 feet under the ground where he spent almost all of his working

life.

To

an outsider who is not bitten by the mining bug, Tom's 32 years as a miner

sound like hell on earth. From

day one he worked at the coal face, lying on his side in a space just 18

inches high giving him just enough room to swing his pick at the narrow

coal seam.

In

addition to the cramped conditions, there was the heat.

The very physical work and the shortage of air at times, deep in

the mine, meant it got very hot for the miners, who used to work in just

their trousers and vests.

In

1951 the picks were replaced by coal cutters, and with the new machinery

came the dust which resulted in the premature deaths of so many miners. At times it was so thick at the coal face that you would not

be able to see a 100 watt bulb nearby.

And

of course, at all times there was the danger.

At any time the rock roof above you could come crashing down.

Your safety depended on your skill in putting in wooden props to

support the roof over the area you were working in.

A

deep rumbling noise like a heavy underground thunder was often a sign that

a collapse was about to occur. But,

then again it was also often a false alarm.

And because the miners were paid by the amount of ore they mined,

some took the risk of continuing to work on when the rumblings came,

rather than rushing out of the area for a false alarm when they could be

mining.

Come

the winter and the miners would only see daylight at the weekends. It would be dark when they entered the mine in the morning

and it would be dark by the time they emerged in the evening.

But

when you have Tom's passion for mining, you don't view the job the same

way. He can honestly put his

hand on his heart and say he enjoyed his 27 years at the Deerpark and his

five years in Ballingarry.

"It's

not the same when you are reared with it" he explained.

"You are born into it like any other trade".

When

he reflects on his life mining, he doesn't dwell on the risks he took.

Instead, he remembers

his workmates. "The

crack we used to have was terrific" Tom remembers.

"They were terribly witty people and it was the crack that

kept us going".

"The

friendship underground was second to none in any other employment.

We were a kind of family and if you were in trouble, I

would come to help you".

The

danger of the job was also balanced out by the fact that you had to be

highly skilled as a miner in that part of the colliery.

"You needed more skill at that, than in any other job in the

world. If you did not know

how to secure yourself, you would not last an hour".

Young

miners learned the skills from senior colliers who were usually family

members. In Tom's case he

spent the first year working with his late brother, John.

The experienced miner would tap the rock over his head and know

where the fractures and weaknesses were, and so where the supports were

needed.

But

just because you were a skilled miner did not mean you could become

complacent about the dangers. In

his 32 years mining, 12 men were killed at the Deerpark.

The figure is low for such a hazardous industry, but it conceals

the large number of injuries suffered.

Broken

bones were common place, with arms and fingers being the most frequent

complaint. Tom himself broke

his arm in three places when he was caught in a roof fall.

But

such dangers did not stop him dicing with death, when he heard the

"thunder" warning sounds. "When

you saw the bits falling from the roof it was time to move out" he

recalls. "But I did

gamble from time to time if it was not too big a rumble".

Mining

has been good to Tom, who lives at the Prince Ground, Castlecomer, with

his wife

"We were always battling for better conditions"

he said, although they were better off than many other workers in similar

occupations. They worked a 42 ½ hour,

five day week, and enjoyed such benefits as coal allowances.

When

the decision was made in 1965 to close the mine, on the grounds that it

was no longer economically viable to extract the ore, the Union stepped in

with their consultant, and it was re-opened after a three month break, with

the aid of Government funding.

But

the writing was on the wall for the Deerpark Colliery.

It continued on until 1969 when the last piece of coal was mined in

Castlecomer and a 300 year tradition came to an end.

The closure left the 300 miners and the town devastated.

Fortunately for Tom he had left the Deerpark in 1966 to take up a

mining job in Ballingarry. However a similar fate followed him there in 1971 when the

mine closed and he was made redundant. He

then worked for Avonmore for 12 years before retiring in 1987.

But

Tom's mining passion still lives on.

He is convinced that if the local mining industry had been

nationalised the mines would still be open today.

He

had high hopes that the State would step in and nationalise the industry

in the mid 1960s. He had been

part of a trade union delegation which had travelled to Dublin to meet the

then Minister for Industry and Commerce,the late Jack Lynch.

The Minister had been sympathetic towards their case until the news

broke that oil had been discovered in the North Sea.

The prospect of cheap British oil swung Lynch away from any

possible programme to Nationalise and develop the Irish coal industry.

With

North Sea oil came the death knell for coal mining in Castlecomer.

Few have mourned its loss more than Tom Brennan. If the mines were

to re-open in Castlecomer tomorrow morning it would take an army of strong men to prevent him from donning his hard hat and heading

underground once more.