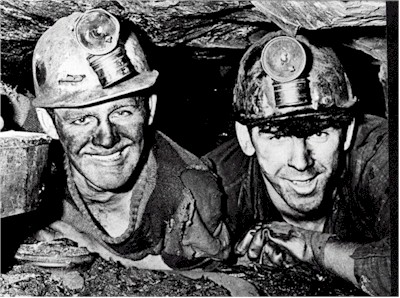

John Delaney (left) and Seamus

Walsh

Working with a coal cutter in an area with a roof space of less

than 2 ft.

Seamus is the Author of " In The Shadow Of The Comer Mines"

This is his Story

In

The Shadow Of The Comer Mines.

My

name is Seamus Walsh, from Castlecomer, formally of the Old-road

Moneenroe- you could say the heart of the coal mining area of Leinster.

All my family worked in the Mines. my father worked there all his life as well as my brothers, PJ and Liam and two of my brothers in law Danny Shalloe and John Delaney.

This

is a true story about a mining family, trying to survive in Moneenroe

nearly forty years ago. Why is there a yearning to go back, to what is

long gone, is it perhaps because part of you, your family, your friends,

men you worked with, laughed and cried with are permanently fossilised '

in the seam of your memory, a seam that is ancient and gone forever, as

that which was plunged, from the depths of the Deerpark Mines.

An

old fisherman looks out to the great mother ocean, not able anymore to

cast his net, yet, those eyes know he has been in touch with life and

death.

So

the miner looks under the great devil earth, he too has been in touch

and is unable to forget.

So

I journeyed out those few miles from Castlecomer along the Clogh Road to

the grave of the Deerpark Mine.

Not

a sinner or soul in sight, but there is a touching here, a slow

unfolding, and gathering, as the bones of the dead

are fleshed with remembering.

I

sit down on a block of stone, and recall all the men and boys who walked

to those famous Bath-Doors, I hear them talking and laughing and see the

miners stitching their clothes, and smell the strong aroma of "

Jiffitex"- the new revolution in clothes mending. I

hear the voices of miners singing, and I

hear the crying of mothers, wives, and girlfriends, when loved

ones failed to come home.

I see my father sitting on

a stool , getting ready to go down in the Mine,

I

hear the noise of the machinery on the land breaker, the washer,

and the screens all-keeping time as they grade the coal for the market.

I rise and walk around the park yard, knowing that beneath my feet, lie

the trapped echoes of another time, a feeling of loneliness filters

through me for, a lot of the men I worked with are now dead and gone,

yet their eyes smile out at me through their noble blackened faces.

I'm up at the mouth of the tunnel now, I

see the wall built up by my father all those years ago. It's very

silent up here but listening carefully I can hear the noise of the pit

below singing back to me, the screeching of the wheels crying out for

the grease, as they carry the big endless rope round and round, while it

carries it's load of coal and stone up to the surface. I

hear the thunder of the empty trams as they make their way down

to the “Big Flat” about three hundred yards below.

I

know this is no ordinary place for these were extraordinary men,

working in awful conditions working deep down in the bowels of the earth

in dirty wet and narrow confines, dark and dangerous for you'd never

know the minute your life would be taken away from you. Only a few yards

from the mouth of the tunnel I see

where the new shaft was built, this was supposed to be the latest

innovation in mining. It was installed by British mining engineers and

proved to be a waste of money, for it seemed the correct site for such a

shaft should have been two miles away in Loon. Though beautifully

constructed it had to be filled in for safety reasons. A lot of work

went into the sinking of the shaft and a lot more to the filling up of

it. In 1970, it was

christened –“The New Shaft" and that's the way it remained.

Coal

has been mined in the Castlecomer area since the early 17th century,

Thomas Wenworth-Head Deputy of Ireland and later to become Lord

Lieutenant and Earl of Strafford invited Christopher Wandesforde, a

gentleman farmer from Yorkshire to Ireland. Wandesforde was made master

of the rolls and was granted a large estate in the Castlecomer area.

When the Earl of Strafford was later tried for high treason and

executed, Wandesford became Lord Deputy for a while. After his death the

land that fell to Wandesforde included the Castlecomer coalfields.

Castlecomer is at the heart of the Leinster coalfield, it took

over the most part of North Kilkenny and also extended into Laois and

Carlow. Nearly all the coal around here is

anthracite with the depths of the seams varying, but most seams

would be only 18 inches high. There was no gas in the mines around

Castlecomer, so in the early times candles were used, stuck in balls of

clay and in later years carbide lamps were used and I

can still smell the carbide even though the pit is closed over

thirty years. The first seam opened by Wandesford was called” The Old

Three Foot" extending from eight to ten square miles, at depths

varying from fifty to one hundred and fifty feet. This method of mining

was to last for nearly one hundred and fifty years. It was estimated in

1875 by a mining engineer called Robert Meadows, that it had produced as

much as 15 million tonnes of coal (that is a huge amount of coal).

The old three-foot seam produced the famous Castlecomer coal,

which was of very high quality- free burning with very low sulphur

content. This seam extended

from Coolbawn to Crettyard and was worked for many years. The

mining method used at the time was called “Bells-pits”. Two shafts

were sunk about fifty yards apart and

were joined by an underground tunnel

The miners would stay down in the mine for up to 8 hours at a

time, digging out the coal from one shaft to another. Explosives were not use at this

time so the coal had to be dug out by hand with picks and wedges. All

big coal would be broken by hammers and wedges for easy loading.

About

the time of the outbreak of the First World War another seam was

discovered in Skehana. The seam was fairly high in places, sometimes

reaching two feet three inches in height, containing a high quality

coal. The Skehana seam worked it's way down to the famous Deerpark

Mines, which opened in 1924. This coal proved to be of very high quality

and was regarded as being the best coal in Europe. By the early 1930’s

there were five major pits in theCastlecomer coalfield.The

“Jarrow" in Clooneen, the “Rock" in Monteen the “Vera”

the “Deerpark" and “Skehana”.

Captain Wandesforde, had great interest in the mines and carried

out considerable expansions and improvements. He had an overhead ropeway

constructed, connecting all the mines so that all coal could be brought

to the Deerpark Colliery from where it would be transported by rail to

Kilkenny.

At

any rate regardless of improvements he was withdrawn and reserved and

regarded by the men as stern and hard. Most of the miners in the 1920's

saw him as their lord and master determining salaries and conditions.

Instead the Wandesford family boasted of not yielding to pressure,

strikes, or conflict of any type. But in the late 1920's and early

thirties there was a lot of unrest about housing, looking for better

conditions in the pit and somewhere to wash because at that time there

were no baths at the mine. After working all day, or night in the mine,

the miners would have to wear their dirty pit clothes home to Moneenroe

and in the winter when there was heavy frost or snow, the clothes would

actually freeze on the men's backs. It really was a tough way of life.

Miners were tough men- they had to be to work in those conditions!

My late father often told me that in their house in the Old road

Moneenroe, where there were

nine brothers and one sister, and next door the Geoghegan family, where

there were also nine brothers and one sister, had between them the

making of a great football team with subs as well as that! All the men

of both families worked in the mines. When the lads came home from work

with their dirty pit clothes on, they would all wash out in the shed at

the back of the house. When

the lads were finished washing themselves their mother would rinse the

heavy dirt off their clothes and bring them into the house with it's big

open fire and two very large hobs. Their clothes would be stacked all

around the fire and some up the chimney to get them dry for the next

days work and at 6.30 the next morning, the lads would grab their

clothes, go out into the yard and bang them off the gable-end of the

house to knock the stiffness out of them. Then they'd get their piece-box(or

lunchbox) and cold bottle of red tea and head up the old road to

Timberoe and go across the Spring Beam Bridge over the river Deen. In

the winter it was bad when the rains came, for it would mean whether

walking or cycling (if you had a bike), when you reached the pit your

clothes would be drenched and you’d have to wear the wet clothes all

day, which wasn’t very pleasant, but, that's the way it was- hardship

after hardship.

In the early thirties the miners were talking about starting a

union in the Deerpark which did not go down well with the mining

company. All they wanted was work, work, work and profit. The clergy in

Moneenroe got news of the union too and again were not pleased with the

idea. When Nixie Boran along with Paddy Carroll and my uncle's Jimmy and

Tom Walsh, formed a branch of the revolutionary workers group, the

miners were invited to send a delegate to the Congress of the Red

International of Labour Unions held in Moscow. Nixie Boran was selected

but was refused a visa by the Government, however he was smuggled out of

the country on a ship containing a cargo of cement and succeeded in

reaching Russia where he stayed for about three months. On his arrival

home the bus on which he was travelling was stopped in Crettyard, and

was boarded by a sergeant and two guards. They took him to the local

barracks at Massford for questioning. He was interrogated about his

visit to Russia and how he got there but he refused to talk to them. The

miners had gathered in their droves outside the barracks and when he

emerged he was cheered and applauded and escorted home in a manner fit

for a hero.

On the following Sunday morning ,the parish priest of Clogh,

preached from the pulpit during mass condemning communism in Moneenroe

and referred to Nixie and his now famous trip to Russia as being

financed by red gold. In the weeks that followed, the priest visited the

schools in Moneenroe and Clogh and spoke to the children about the evils

of Russian Communism. Just imagine how the children felt shaking in

their boots with this man shouting at them. The following Sunday Nixie

held a meeting in his native Moneenroe where he gave a detailed account

of what he saw and learned in Russia. From then on, Nixie devoted his

time and energy to the foundation of a miner's union. The union was

launched on 30th November 1930 in Moneenroe - the heart of

the mining district. Nixie wrote regularly in the "Workers Voice'

on the working and living conditions of miners living in the area. In

Timberoe for instance, some miners were living in wooden huts with sheet

iron roofs that were full of holes. The inside walls were plastered with

mud to keep some heat in the house but when it rained the water would

come in through the roof, and washed the mud all over the floor. It goes

without saying, that this was none too pleasant on a cold wet winters

evening.

Miners were not getting any ration of coal at this time. The fuel

they used was cannels and homemade bombs. Cannels was a stone with some

coal running through it and had to be broken into small pieces for

burning. The homemade bombs were made from culm bought for three-pence a

hundred weight. This is where

the women came into their own as they were the experts at making the

culm bombs. It was known in the Castlecomer area as “dancing” a

batch of culm. You would get a hundred weight of culm (or fine dust),

yellow clay and water sprinkled with a little lime, to hold them

together. The dance would start and last about 15-20 minutes. I can see

my mother now, in a big pair of Wellington boots singing as she

made the bombs, a woman like so many of her generation adapting

as best she could to the tough times that prevailed. But change would

have to come, for people deserve to be treated fairly and with dignity

for the work they did. The miners were starting to get uneasy and the

mine and quarry

In the autumn of 1932, things were bad at the colliery with the

management claiming that there was no sale for the coal that was piled

high in the pit yard while miners continued to work a two day week. The

trammers threatened to strike unless there was a wage increase of three

pence a ton and Nixie handed in notice to this effect.

Around this time there was an increase in union membership and

the men were getting very uneasy, however, the company reacted by

ignoring the strike threat and made no offers to the miners. Nixie wrote

that there was widespread discontent and that the trammers were

especially unhappy. He also claimed that the rates in the Jarrow and

Skehana mines fell well short of what they were looking for. The company

continued to ignore the unions threats and demands and on October 17th

1932 an all out strike of the four hundred miners came about, the strike

began with a militant flourish, but soon the men and their families were

in difficulties because the union had no funds and by the third week the

strikers were feeling the pressure. Local shopkeepers were canvassed for

food and money and collectors were sent out to look for and organise

support. Peadar O' Donnell, approached some of the bakeries in Dublin

and two carloads of bread were delivered to the miners.

The Dublin Trades Council on the other hand refused assistance

because the union was not affiliated to congress. In an attempt to

settle the dispute, the Department of Industry and Commerce, invited

Nixie and other mining leaders, to a meeting in Dublin. The Department

officials suggested a return to work pending a conference of all

concerned. The strike committee would not agree to this and no agreement

was reached. Peadar

O'

Donnell urged support for the strikers at street meetings in Dublin. The

strike committee appealed to the nations newspapers for awareness and

help. The strikers were said to be fighting in their bare feet and

further appeals were made to workers and republicans to support them.

Writing in "An Phoblacht', Peadar O'Donnell said that four hundred

Irish families had been flung out on the scrap heap, crying out for

help. The men in their sixth week of strike were without food and money.

The Government sent in two mediators, which consisted of the Labour T.

D.Mr. Gavin and Fianna Fail

T.D. Mr. Gibbons.

From the discussions that followed with both sides in the dispute, two resolutions arose and were put to the striking miners. The first which was defeated, was that the men would return to work pending a conference. The second which was carried, was that there would be no return to work without some agreed increase in tonnage rates. After further discussions the company offered an increase of a half penny in tonnage rates. This offer was put to the men and was accepted- the strike was over! The union leaders boasted of the miner's glorious victory when there was in fact very little glory. The strikers had been brought to their knees through lack of funds and were glad to get back to work with a small bit of dignity. The strike however, had some very important long-term effects. It had brought miners closer together to form a bond that would last until the pit closed down in 1969. Flushed with success as they saw it, and with this new- found confidence, the union committee began to discuss the building of a workers hall as, during the strike they had to hold their meetings in the open air. The miners were very angry at the fact that they contributed to the building fund of the school and new church in Moneenroe, which had been officially opened by the Bishop Dr. Collier two years previously. They were determined that in the future, they would not be dependant on the clergy for a meeting place. This angered the clergy very much but the miners were determined to continue with their struggle for their rights. Even when Fr. Cavanagh was transferred to Kilkenny, he still spoke out against the miners but he wasn't working underground in a dark hole

I often sat in an empty round of trams going down the main drift to

the

There were many very bad accidents in the Deerpark mine, hundreds

of men were maimed, and scared for life, fourteen people at most lost

their lives in the mine, and many more died on the account of the injuries

they received. The first man to get killed in the mine was Martin Brennan,

of Gazebo , Moneenroe in the early 193O's.

Joe Brennan (Durrick) commonly known as Bosy was hit by a wagon in

the yard and he wasn't even working in the mine, he was just over from the

Old road Moneenroe getting a ration of coal for his parents, when he was

killed. A lot of these men

who were badly hurt never

returned to work the coal again, the compensation they received was very

little £4-10 shillings a week even if you had 10 children or none at all

you would still get the same amount.

Ned Kelly from the Old Road Moneenroe was the last to be killed in

the Deerpark mine, he was just a few months short of his 16th.

birthday and 1 remember it as if it was yesterday. It was the 1st.

day of April 1960 late on a Friday afternoon. We were getting dressed to

go home when news came filtering through that there was a bad accident

down in the mine. I can still picture the miners faces, the shock and

worry in their eyes as if to say "oh no, not again, it can't be

true" but it was true, as Johnny Brennan (Jingler), came running down

the baths floor, and told us the dreadful news about poor Ned Kelly. Ned

was caught in the face engine, in a place called the fault about two miles

from the mouth of the tunnel. I raced home to tell my mother as she was

very friendly with Mrs. Kelly (Ned's mother).

When she heard the news, she just froze and thought it was an April

fools joke but when she saw Fr. Lougry come into the yard her screams will

remain with me forever.

A doom and despair born of a sense of helplessness, for we all knew

the dangers of mining, but had to live in a certain sense of denial in

order to keep going and it was traditional for all Deerpark miners not to

return to work until the man or boy was laid to rest.

Rats

were a big problem in the pit too, they were bigger than the rats you

would see on the surface, you could not leave your lunch down, or they

would eat it upon you, that's why the miners always had peace-boxes to

hold their lunches. There was plenty of clear spring water down in the

mine but it was too dangerous to drink, for the rats would have urinated

in it and you could easily pick up that fatal disease known as "Weils’

Disease".

Miners also suffered a lot with bad chests especially those who had

been working on the coal face for many years, the disease conceived from

these conditions, was known as "Pneumoconiosis", the bane of

coalminers lives. Pneumoconiosis was not made an industrial disease until

1971, too late for a lot of miners who were dead and gone.

When the mines closed down in 1969 the miners got just one weeks

The last efforts by the management and union to save the

Castlecomer

Friday night, the 23rd. of July 1999 was a very special

night for my family

The

miners were great men, I was proud to be a miner, and a miner's son. It

was in the blood, and you could do nothing about it.

In the Shadow of the Mines is on sale in Castlecomer, and Kilkenny

or from myself in Castlecomer, at 056-41504.

It's a good read, a study of mining, and social history of

Castlecomer.

(The

miners really were a breed apart), so with the help of my book “In the

Shadow of the Mines”, the great Deerpark Miners will never be forgotten.